Piece of Art Appears to Have Been Created to Mark the Unification of Egypt?

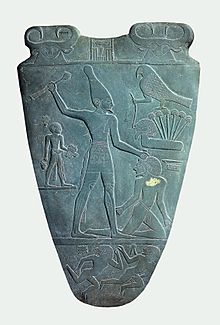

| Narmer Palette | |

|---|---|

Both sides of the Narmer Palette | |

| Material | siltstone |

| Size | c. 64 cm × 42 cm |

| Created | 3200–3000 BC (circa) |

| Discovered | 1897–1898 |

| Present location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

| Identification | CG 14716 |

The Narmer Palette, also known equally the Great Hierakonpolis Palette or the Palette of Narmer, is a significant Egyptian archeological find, dating from nearly the 31st century BC, belonging, at least nominally, to the category of cosmetic palettes. Information technology contains some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions ever institute. The tablet is thought by some to depict the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the rex Narmer. On one side, the king is depicted with the bulbed White Crown of Upper (southern) Arab republic of egypt, and the other side depicts the king wearing the level Ruby Crown of Lower (northern) Egypt. Along with the Scorpion Macehead and the Narmer Maceheads, also plant together in the main deposit at Nekhen, the Narmer Palette provides one of the earliest known depictions of an Egyptian rex. The Palette shows many of the archetype conventions of Ancient Egyptian art, which must already have been formalized past the time of the Palette's creation.[ane] The Egyptologist Bob Brier has referred to the Narmer Palette equally "the first historical document in the world".[2]

The Palette, which has survived five millennia in almost perfect status, was discovered past British archeologists James E. Quibell and Frederick W. Green, in what they called the Main Deposit in the Temple of Horus at Nekhen, during the dig season of 1897–98. [3] [4] [5] Also found at this dig were the Narmer Macehead and the Scorpion Macehead. The verbal identify and circumstances of these finds were non recorded very clearly by Quibell and Green. In fact, Green's report placed the Palette in a different layer i or two yards away from the deposit, which is considered to be more than authentic on the ground of the original excavation notes.[vi] It has been suggested that these objects were royal donations made to the temple.[7] Nekhen, or Hierakonpolis, was 1 of four power centers in Upper Arab republic of egypt that preceded the consolidation of Upper Egypt at the cease of the Naqada III period.[8] Hierakonpolis's religious importance connected long after its political role had declined.[nine] Palettes were typically used for grinding cosmetics, but this palette is too large and heavy (and elaborate) to have been created for personal utilise and was probably a ritual or votive object, specifically fabricated for donation to, or use in, a temple. Ane theory is that it was used to grind cosmetics to adorn the statues of the deities.[10]

The Narmer Palette is part of the permanent drove of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[eleven] It is one of the initial exhibits which visitors have been able to see when entering the museum.[xi] It has the Periodical d'Entrée number JE32169 and the Catalogue Général number CG14716.

Clarification [edit]

Serekhs bearing the rebus symbols northward'r (catfish) and mr (chisel) inside, existence the phonetic representation of Narmer's proper name[12]

The Narmer Palette is a 63-centimetre-tall (2.07 ft), shield-shaped, ceremonial palette, carved from a single piece of flat, soft nighttime gray-green siltstone. The stone has often been wrongly identified, in the past, as being slate or schist. Slate is layered and decumbent to flaking, and schist is a metamorphic rock containing big, randomly distributed mineral grains. Both are unlike the finely grained, hard, bit-resistant siltstone, whose source is from a well-attested quarry that has been used since pre-dynastic times at Wadi Hammamat.[thirteen] This material was used extensively during the pre-dynastic period for creating such palettes and also was used as a source for Erstwhile Kingdom bronze. A statue of the 2d dynasty pharaoh Khasekhemwy, found in the same complex as the Narmer Palette at Hierakonpolis, too was made of this material.[xiii]

Early hieroglyphic symbols on the Narmer Palette

Both sides of the Palette are busy, carved in raised relief. At the acme of both sides are the central serekhs begetting the rebus symbols north'r (catfish) and mr (chisel) within, existence the phonetic representation of Narmer's proper name.[12] The serekh on each side are flanked by a pair of bovine heads with highly curved horns, thought to represent the moo-cow goddess Bat. She was the patron deity of the seventh nome of Upper Egypt, and was too the deification of the cosmos inside Egyptian mythology during the pre-dynastic and Former Kingdom periods of Ancient Egyptian history.[fourteen]

The Palette shows the typical Egyptian convention for of import figures in painting and reliefs of showing the striding legs and the head in contour, but the body every bit from the front. The canon of trunk proportion based on the "fist", measured across the duke, with xviii fists from the ground to the hairline on the forehead is also already established.[15] Both conventions remained in utilise until at least the conquest by Alexander the Great some 3,000 years later. The minor figures in agile poses, such as the king's convict, the corpses and the handlers of the serpopard beasts, are much more freely depicted.

Recto side [edit]

Equally on the other side, two human being-faced bovine heads, thought to represent the patron cow goddess Bat, flank the serekhs. The goddess Bat is, every bit she often was, shown in portrait, rather than in profile as is traditional in Egyptian relief carving. Hathor, who shared many of Bat'due south characteristics, is often depicted in a similar way. Some authors[ which? ] advise that the images represent the vigor of the king as a pair of bulls.[ commendation needed ]

A large picture in the centre of the Palette depicts Narmer wielding a mace wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt (whose symbol was the flowering lotus).[ citation needed ]

Detail of the Narmer Palette showing a belt with 4 beaded tassels and a fringe at the back representing a lion's tail.

Fastened to the belt worn by Narmer are four beaded tassels, each capped with an decoration in the shape of the head of the goddess Hathor. They also are the same heads as those that adorn the meridian of each side of the palette. At the dorsum of the belt is attached a long fringe representing a lion's tail.

On the left of the king is a homo bearing the king's sandals, flanked past a rosette symbol. To the right of the king is a kneeling prisoner, who is about to be struck by the rex. A pair of symbols appear next to his head perhaps indicating his name (Launder) or indicating the region where he was from.[ commendation needed ] Above the prisoner is a falcon, representing Horus, perched to a higher place a set up of papyrus flowers, the symbol of Lower Arab republic of egypt. In his talons, he holds a rope-like object which appears to be attached to the olfactory organ of a man's head that also emerges from the papyrus flowers, perhaps indicating that he is drawing life from the caput.[ commendation needed ] The papyrus has oft been interpreted[ by whom? ] as referring to the marshes of the Nile Delta region in Lower Egypt, or that the battle happened in a marshy area, or even that each papyrus flower represents the number one,000, indicating that 6,000 enemies were subdued in the boxing.[ citation needed ]

Verso side [edit]

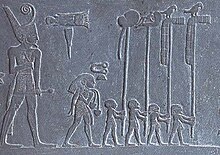

Beneath the bovine heads is what appears to be a procession. Narmer is depicted at nearly the full pinnacle of the register, emphasizing his god-like status in an artistic practice called hierarchic scale, shown wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt, whose symbol was the papyrus. He holds a mace and a flail, two traditional symbols of kingship. To his correct are the hieroglyphic symbols for his name, though not contained within a serekh. Backside him is his sandal-bearer, whose name may be represented by the rosette actualization adjacent to his head, and a second rectangular symbol that has no articulate estimation, only which has been suggested may stand for a town or citadel.[sixteen]

Immediately in front end of the pharaoh is a long-haired man, accompanied by a pair of hieroglyphs that have been interpreted as his name: Tshet (this assumes that these symbols had the same phonetic value used in after hieroglyphic writing).[ citation needed ] Before this human being are 4 standard bearers, belongings aloft an animate being skin, a dog, and two falcons. At the far correct of this scene are ten decapitated corpses with heads at their feet, maybe symbolizing the victims of Narmer's conquest.[ citation needed ] Above them are the symbols for a ship, a falcon, and a harpoon, which has been interpreted[ by whom? ] equally representing the names of the towns that were conquered.

A detail from the Narmer Palette, with the oldest known depiction of vexilloids.

Below the procession, 2 men are holding ropes tied to the outstretched, intertwining necks of two serpopards confronting each other. The serpopard is a mythological fauna, a mix of serpent and leopard. The circle formed by their curving necks is the central part of the Palette, which is the area where the cosmetics would take been basis. Upper and Lower Egypt each worshipped lioness war goddesses as protectors; the intertwined necks of the serpopards may thus represent the unification of the country. Similar images of such mythical animals are known from other contemporaneous cultures, and in that location are other examples of late-predynastic objects (including other palettes and knife handles such equally the Gebel el-Arak Knife) which borrow like elements from Mesopotamian iconography, suggesting Egypt-Mesopotamia relations.[17]

At the bottom of the Palette, a bovine image is seen knocking downward the walls of a urban center while trampling on a fallen foe. Because of the lowered head in the image, this is interpreted as a presentation of the king vanquishing his foes, "Bull of his Female parent" being a common epithet given to an Egyptian king as the son of the patron cow goddess.[18] This posture of a bovine has the meaning of "force" in later hieroglyphics.

Scholarly debate [edit]

The Palette has raised considerable scholarly debate over the years.[19] In general, the arguments fall into 1 of two camps: scholars who believe that the Palette is a record of an of import consequence, and other academics who contend that it is an object designed to establish the mythology of united rule over Upper and Lower Egypt by the king. Information technology had been thought that the Palette either depicted the unification of Lower Egypt by the male monarch of Upper Arab republic of egypt, or recorded a recent war machine success over the Libyans,[twenty] or the last stronghold of a Lower Egyptian dynasty based in Buto.[21] More than recently, scholars such equally Nicholas Millet accept argued that the Palette does non represent a historical outcome (such as the unification of Egypt), but instead represents the events of the year in which the object was defended to the temple. Whitney Davis has suggested that the iconography on this and other pre-dynastic palettes has more to do with establishing the rex equally a visual metaphor of the acquisition hunter, caught in the moment of delivering a mortal accident to his enemies.[22] John Baines has suggested that the events portrayed are "tokens of majestic achievement" from the past and that "the chief purpose of the piece is not to record an consequence but to affirm that the king dominates the ordered world in the proper name of the gods and has defeated internal, and especially external, forces of disorder".[23]

In popular culture [edit]

The Narmer Palette is featured in the 2009 film Watchmen equally ane of the Egyptian objects that are present in Ozymandias'due south office. The Australian writer Jackie French used the Palette, and recent research into Sumerian trade routes, to create her historical novel Pharaoh (2007). The Palette is featured in manga artist Yukinobu Hoshino'south short story "The temple of El Alamein". The Palette is also featured in The Kane Chronicles by Rick Riordan where the palette is fetched by a magical shawabti servant. In Ubisoft's 2017 game Assassinator's Creed Origins, the Palette is a quest item and minor plot betoken toward the end of the master quest's storyline. The Narmer Palette is a main plot point in Lincoln Child'southward The Tertiary Gate novel, in which they attempt to find the tomb of king Narmer in the Sudd.

See besides [edit]

- Listing of ancient Egyptian palettes

- Libyan Palette (some other well-known Predynastic Egyptian palette)

- Warka Vase (a comparable contemporaneous work of narrative relief sculpture from the Sumerian civilisation)

- Kish tablet

References [edit]

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. p.6 Routledge, London. 1999. ISBN 0-203-20421-2

- ^ Brier, Bob. Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians, A. Hoyt Hobbs 1999, p.202

- ^ [1] J. E. Quibell, Hierakonpolis pt. I. Plates of discoveries in 1898 past J. Eastward. Quibell, with notes by W. Chiliad. F. Petrie, Quaritch, 1900

- ^ [ii] J. Due east. Quibell, Hierakonpolis pt. Two. Plates of discoveries, 1898–99, with Description of the site in detail, by F. W. Light-green., Quaritch, 1902

- ^ The Aboriginal Arab republic of egypt Site – The Narmer Palette Archived 2006-06-15 at the Wayback Machine accessed September xix, 2007

- ^ Shaw, Ian. Exploring Ancient Egypt. p.33 Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. The Emergence of the Egyptian State, in The Oxford History of Aboriginal Arab republic of egypt. Ed. Ian Shaw, p.61. Oxford Academy Press, 2000

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 36–41. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWilkinson1999 (help)

- ^ Friedman 2001, pp. 98–100, book ii.

- ^ Bramble, Bob. Cracking Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt, The Great Courses lecture series

- ^ a b Shaw, Ian. Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction. p.iv. Oxford Press, 2004.

- ^ a b Wengrow, David, The Archaeology of Aboriginal Egypt Cambridge University Printing, ISBN 978-0-521-83586-2 p.207

- ^ a b Shaw, Ian. Ancient Arab republic of egypt: A Very Curt Introduction. pp.44–45. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Aboriginal Egypt, p.172 Thames & Hudson. 2003. ISBN 0-500-05120-8

- ^ Smith, Westward. Stevenson, and Simpson, William Kelly. The Art and Compages of Ancient Egypt, pp. 12–thirteen and annotation 17, 3rd edn. 1998, Yale University Press (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0300077475

- ^ Janson, Horst Woldemar; Anthony F. Janson History of Fine art: A Survey of the Major Visual Arts from the Dawn of History to the Present Day Prentice Hall 1986 ISBN 978-0-xiii-389321-2 p.56

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. p.half-dozen, Routledge, London. 1999. ISBN 0-203-20421-2.

- ^ Breasted, James Henry. Ancient Records of Egypt, Chicago 1906, part Two, §§ 143, 659, 853; part Three §§ 117, 144, 147, 285 etc.

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan, 2017. "Narmer Palette Bibliography"

- ^ Shaw, Ian and Nicholson, Paul. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. p.197 Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1995. ISBN 0-8109-9096-ii

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. p. 40. Routledge, London. 1999. ISBN 0-203-20421-2

- ^ Shaw, Ian. & Nicholson, Paul. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, pp. 196–197. The British Museum Press, 1995.

- ^ Baines, John "Communication and display: the integration of early Egyptian art and writing" Artifact, vol. 63:240, 1989, pp. 471–482.

Bibliography [edit]

- Brier, Bob. The Offset Nation in History. History of Ancient Arab republic of egypt (Audio). The Teaching Visitor. 2001.

- Friedman, Renée (2001), "Hierakonpolis", in Redford, Donald B. (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 98–100, volume 2 .

- Hendrickx, Stan (2017), Narmer Palette Bibliography (PDF) .

- Kinnaer, Jacques. "What is Actually Known Virtually the Narmer Palette?", KMT: A Mod Journal of Ancient Arab republic of egypt, Spring 2004.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18633-1.

- Grimal, Nicolas Christophe A history of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell, London 1996, ISBN 0-631-19396-0.

- Kemp, Barry J. (May 7, 2007). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation. London: Routledge. p. 448. ISBN978-0-415-23550-ane.

- Davis, Whitney Masking the Blow: The Scene of Representation in Late Prehistoric Egyptian Art. Berkeley, Oxford (Los Angeles) 1992, ISBN 0-520-07488-2.

Farther reading [edit]

- Bard, Kathryn A., ed. Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge, 1999.

- Brewer, Douglas J. Aboriginal Egypt: Foundations of a Civilization. Harlow, UK: Pearson, 2005.

- Davis, Whitney. Masking the Blow: The Scene of Representation In Tardily Prehistoric Egyptian Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- Lloyd, Alan B., ed. A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Chichester, U.k.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

- Málek, Jaromír. In the Shadow of the Pyramids: Egypt during the Erstwhile Kingdom. Norman: University of Oklahoma Printing, 1986.

- Redford, Donald B., ed. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. 3 vols. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Shaw, Ian. Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Shaw, Ian, and Paul Nicholson. The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Rev. ed. London: British Museum, 2008.

- Wengrow, David. The Archaeology of Early on Egypt: Social Transformation in North-Due east Africa, ten,000 to 2650 BC. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Wenke, Robert J. The Ancient Egyptian Country: The Origins of Egyptian Culture (c 8000–2000 BC). Cambridge, United kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Wilkinson, Toby. Early on Dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge, 2001.

External links [edit]

- Expert images of Narmer Palette Scroll down to the drawing of the Palette and accept the link to the photographs published by Francesco Rafaele.

- The Narmer Palette: The victorious king of the southward

- Narmer Palette (weber.ucsd.edu)

- Narmer Palette (ancient-egypt.org)

- Corpus of Egyptian Late Predynastic Palettes Images of more than 50 such palettes with diverse motifs

- Narmer Catalog (Narmer Palette)

Coordinates: 30°02′52″Due north 31°14′00″E / 30.0478°N 31.2333°E / 30.0478; 31.2333

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narmer_Palette

0 Response to "Piece of Art Appears to Have Been Created to Mark the Unification of Egypt?"

Post a Comment